- Home

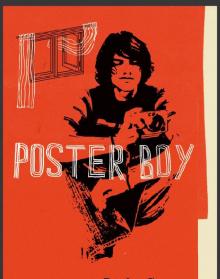

- Dede Crane

Poster Boy Page 2

Poster Boy Read online

Page 2

I plugged in the waffle iron. “Stink.”

“Nail polish,” said Mom, sliding open the deck door.

“I painted the nails on Dad’s new girl hand,” said Maggie, picking it up and thrusting it in my direction. “Need a hand with those waffles?”

Dad was a bio-mechanic up at the university. Prosthetics. Made myoelectric hands. A creepy way to make a living, but somebody had to do it. We had a lot of bad hand jokes in our family.

Maggie scratched her head with the nails of the rubber hand.

“Dad thinks I should do my science project on how negative and positive intention influences the vibrational level of matter.”

I had no clue what my sister the geek had just said. I was allergic to science fairs and glad as hell those days were behind me. Dad, Mr. Myoelectric, used to be keen to help with my projects, too. He’d come up with something using hot wires and electric currents — things that could kill you if you touched the wrong ends. As he did the bulk of my project, I would stand real close as if I was doing it, too. He’d explain stuff and I’d not understand it but write it down word for word. I’d get a blue ribbon and feel like a guilty-ass cheater.

“This Japanese scientist, Dr. Emoto,” explained Dad, “has experimented with exposing water to various stimuli and taking microscopic photos of the crystals that form when that water’s frozen. It’s really pretty fascinating.”

I caught Mom’s eye and she smiled.

“I bet you didn’t know trees are eighty percent water?” said Maggie.

“Did,” I lied.

Like Dad, Maggie went gaga over the factual world — why bees swarmed, why leaves changed color, how tiny worms set up house at the base of each eyelash, Guinness world records.

Like Mom, I preferred the abstract. She’d gone the art college route. Used to be into drawing and painting, but when I was maybe two, she got turned onto silkscreen — a method of printing ink designs on fabric. She started off selling scarves and stuff at craft fairs, later to boutiques. But in August she scored her first big commission: a dozen silkscreen banners for the new bank coming to Jackson Street in the spring. Danced around the house for a week.

My thing was photography, though I didn’t know if I was any good. I went roaming with Davis, took pictures of whatever caught my eye. Clouds were cool, doorknobs, close-ups of rusted things, and trees at night. But then, smoking a little weed made everything look cool.

“He’s exposed water to Beatles music, Beethoven, Elvis, acid rock,” continued Dad. “You should really see some of these photos, Gray.”

Later, I thought, not responding. Not responding was often simplest.

“The acid rock photos didn’t form any crystals at all,” said Maggie. “They’re just these blobs.”

“What are you up to today, Gray?” asked Mom.

“Stuff.”

“What time do you work?”

“Five.” I worked Wednesdays and Saturdays at the Cineplex. Selling tickets, filling bottomless buckets of popcorn and Coke, sweeping candy wrappers off the floor. The job was a job but I got to preview movies, invite a friend. I was saving for some beater van, seventies style, mattress in the back. Wanted a car you could travel in.

Only problem was I always needed stuff — clothes, shoes or delish foot-longs from Safeway — so hadn’t saved more than a few hundred.

“Need a ride?” asked Mom.

“Sure.”

“You can practice driving.”

I grunted. I’d just got my Learners.

“Take a vitamin C with your breakfast. Maggie’s coming down with a cold.”

“My leg aches.” Maggie rolled her eyes. “You don’t get a cold in one leg.”

“Just to be safe.”

Mom was an involved parent. Had the maternal instincts of a moose, claimed Dad. Mother moose, according to him, were the most deadly animals on the planet.

Mom turned to me. “How was the party?”

“Fine.” I was concentrating on filling all the squares of the waffle iron with just the right amount of batter, otherwise it spilled over when you closed the top.

“Don’t forget you have to do your bathroom before you go anywhere.”

“Yeah.”

“My son speaks in single word sentences,” sighed Dad.

“Chimpanzees can give single word responses,” said Maggie.

“My point exactly.”

“He’s sixteen,” said Mom.

“You’d think he’d have learned to speak by now,” said Dad.

“Just remember when you were sixteen,” said Mom.

“I was a nerd, remember?”

“Was?” I said.

Dad and Mom both laughed and I couldn’t help smiling. For some reason it feels dope to make your parents laugh.

“Good one, Gray,” said Dad. “A single word with some punch. Nerds made your precious computer and Xbox, don’t forget.”

“Cool nerds,” I said.

“Ooh, two words together,” said Dad. “He gets a banana.”

“I don’t know why people think being dumb is cool,” said Maggie. “Like what Hughie did last night.”

“What did Hughie do last night?” asked Mom.

“Nothing,” I said, meeting Maggie’s eye.

“Nothing,” said Maggie and gave me a you-owe-me smile.

Mom asked Dad what he thought of her fabric choice. He said something nice and she kissed his head.

When I compared my parents to my friends’ parents, who criped and yapped at each other, had affairs or drank too much, half of them separated or divorced, I might say they got on famously. Davis, for example, had a total of three moms and two dads. Go figure. But according to him none of them got on any better than the last. His various parents would fight even in front of guests, namely me. And with their kids.

I once saw his dad slap Davis across the face for some “smart ass” remark — though I think Davis was sincerely trying to be funny. It was a hard hit, too. Davis’s cheek was red for the rest of the day. Though it could have been from embarrassment. It’s shitty enough to get face-slapped but a whole lot shittier in front of a friend. Davis didn’t tell a joke for a week.

“Mag,” said Mom, “I’m going to have some leftover fabric. You could silkscreen some scarves. Would make nice Christmas gifts for your teachers?”

“I have only one female teacher,” corrected Maggie.

“Ties, then?”

“Sure.”

If it wasn’t for the scary cleaning people, I would have taken my waffles downstairs to eat at the computer. Instead I was forced to sit at the kitchen table and look at a photo of a six-sided water crystal formed after being exposed to Elvis singing “Heartbreak Hotel.” It actually looked like two crystals mushed together.

“The crystal’s broken apart,” said Maggie, awed.

“I’ll be damned,” said Dad.

3 Girlfriends

Trig class. I was on top of it at the beginning of the year, sort of, but in the past few weeks I’d gone into a kind of coma.

The bell rang. I looked at the assignment on the board, then at my notes. There on the page were detailed drawings of sushi.

Trig was the last class before lunch. I looked back at the board.

I couldn’t ask Hughie to decipher the assignment because I’d heard him snoring behind me during class. Then I noticed that Ciel chick copying down the homework as if she understood it. I went over to her desk.

“Hey, Ciel. How’s it going?”

She kept writing.

“It’s Gray, remember me from — ”

“I do.” She didn’t sound thrilled by the memory.

“Great shirt,” I said before I noticed how plain it was. A black T-shirt.

She gathered her books to leave.

“Do you actually understand this stuff?”

“I do.” She razored me with those eyes of hers. Brown, I noted, with copper rings around the pupil.

“I kind of get it, but missed a few things today.” I put on my hangdog face. “Would you mind, horribly, explaining it to me over lunch?”

“Me, too?” said Hughie suddenly beside me, his hair all sleep-wrecked.

“If you buy me a Caramilk bar from the vending machine.” She smiled. A greedy sort of smile.

“Yeah, sure.”

She looked at Hughie. “Two.”

“Oh. Okay,” agreed Hughie.

She went on ahead and we followed like sheep.

“Two what?” whispered Hughie.

We had a “study-lunch” with Ciel once a week after that. The rest of the week’s lunchtimes, I either played soccer Frisbee with the guys or hung with Natalie and her friends.

Ciel and Natalie had gone their separate ways. Ciel now hung with the band types and the environmental club — the Turn-Off-Your-Lights-to-Save-the-Marmot Club as Davis called it.

Lucky for Hughie and me, Ciel was Maggie-smart. Not a lot of humor going on, but she had a very clear way of explaining things. She didn’t linger, didn’t take questions, and never ate her Caramilks in front of us. I imagined them stacked under her bed like gold bars.

Just before Christmas break we had a major quiz worth twenty percent of our mark, so I invited her to my house to “study” with me and Hughie. Sounded less desperate than “teach us everything now.” Our books spread out on the floor of my sweet, she summarized trig facts as if it was idiot proof and then tried, not very successfully, to hide her impatience when we needed stuff repeated.

But I found studying her more interesting. The way she held her head so erect I wanted to balance a book on it. And how her brown hair had these hidden gold strands when the light hit it, and the slight hollows under her cheekbones held tiny shadows. As she explained the differences between sine, cosine and tangent, I thought how Natalie’s body curved like hill and valley while Ciel’s was like water flowing gently downhill. How Natalie’s body was pop music and Ciel was that lyrical jazz stuff Dad listened…

“Gray?”

“Huh?” I removed my eyes from her butt.

“Are you with us?” asked Ciel.

“I’m getting it,” I nodded. She looked doubtful. “Go on,” I said.

I watched the intensity in her face as she wrote out the equation “the ratio of the side opposite a given angle to the hypotenuse” like a magnifying glass focusing sunlight. I imagined a brown spot appearing on the white page of the textbook, then a searing hole, the brown edges spreading outward, the book bursting into…

“So what would you use to solve this problem? Sine or cos?” Ciel looked directly at me, blinding me with her Super Sight.

“It’s Hughie’s turn to answer,” I said, looking at Hughie.

“What?” said Hughie.

“Come on, man, pay attention,” I said. “One more time for Hughie here.” I shook my head apologetically.

She sighed. “Do you guys really want to pass this class?”

“Yes,” we said in chorus, because to have to take trig all over again next semester would be self abuse.

And not the good kind.

Hughie took his Caramilk bar from his jacket pocket.

“Want this now?”

“No,” she said and started from the top.

* * *

Thanks to Ciel, I passed the quiz. Hughie, too. Not by much, but we passed. The next day was the Christmas Red and Green dance. Boo yeah. Dances at our school kicked ass. I’d bought a red shirt at American Eagle, stuffed a little pine branch in my pocket, sprinkled gold glitter in my hair.

The night of the dance, Davis got a friend of his brother’s to buy us some beer which he, Hughie and I drank behind the baseball bleachers beforehand. The ground was all crunchy, our breath cartoon clouds.

Hughie wore a green tunic and tights like Will Ferrell in Elf. He had a spliff taped behind the red feather in his green cap.

“This stuff is dank,” said Hughie, lighting up.

“I got some seeds from my half-sister’s boyfriend’s brother,” said Davis. “I’m going to grow me some blazing, ripping, danking, Mary Jane-me-up-the-ass weed.”

“Have you ever grown anything?” I laughed.

“My dick.”

God, I loved Davis.

We all took one good hit. Then Hughie snuffed it and re-taped it inside his feather.

It was a nice high, all sparkly like the December night. It gave me a feeling of belonging to something bigger than myself, and I could actually relax a little. Or maybe that was the beer part. There were some cool ragged clouds wrapped around a half moon. The more I looked at it, the more I could swear it made the perfect profile of our science teacher, Mr. Sneddon.

I nudged Davis and pointed. “Mr. Sneddon.”

He looked up and laughed.

“Yeah, yeah,” he said, and I was sure he understood.

“If only I had my camera.”

“Yeah,” said Davis, and we walked toward the gym.

I was feeling fine as I headed inside to meet Natalie. Saw her in the ticket line with Erin. Skin tight and satiny, her dress was Christmas-ball red and man, did it stimulate. It hung off one shoulder, toga style, and was cut low in the front. A mini cheering section in my head chanted, CLEA-VAGE… CLEA-VAGE… CLEA-VAGE.

When she saw me looking, she did a little turn on her black heels.

“You like?”

“Wow!” I tried to lift my eyes from her chest to her face but they moved at mud speed.

“She made it herself,” said Erin. “In Sewing.”

“Yeah,” I said. In that moment I felt totally in love, not only with Nat but with kowtowing Erin and the ticket sellers, the frowning principal, Ms. Jackson, standing behind them — even the macho jocks laughing down the hall.

“Let’s see what you’re wearing,” demanded Nat, and I obediently took off my jacket.

She turned up the collar of my shirt. “You look good in red, Gray Fallon.”

“You…” was all I managed.

“American Eagle… nice. And I like the shoes.”

I’d also bought a new pair of off-white skate shoes.

And then, feeling like I’d passed some final test, she slipped her arm in mine, leaned her beautiful head on my shoulder and provided me a direct view down the cleave tunnel.

The DJ was excellent, playing a good range of stuff and not just all techno. A highlight of the evening was getting further acquainted with Natalie’s breasts in the equipment room. As long as I didn’t mess up her hair or make-up, she didn’t seem to mind.

It amazed me that her chest was so radically different from my own. Ridiculously soft, those two things. Quiet, too, unlike Natalie who, between kisses, kept talking about Erin liking some tenth grader named Erin, too, only spelled Aaron.

“That’ll be so weird if they go out. Or got married. Wouldn’t that be too funny?”

As the dance wound down, I thought to look for Ciel, thank her for the miracle of me and Hughie passing that quiz. It was a strategy move, since I’d need her help even more come final exams.

I asked Natalie if she’d seen her.

“She didn’t come. Had some concert thing.” She rolled her eyes.

I was supposed to work at the theater but had called in sick.

“What sort of concert?” I asked, picturing Ciel playing my guitar.

“My mom’s like in love with Ciel,” Natalie went on. “Thinks she’s the perfect child. I hate that when your parents think somebody else’s kid is so great. It’s like the

y want to trade you in.”

“I mean what instrument does she play?”

“The harp.” Nat made a face. “Who plays the harp?”

“Angels?” I said, as Erin and Chrissy rushed over all frantic and pulled Natalie away to share some gossipy secret.

Walking home that night, the dope and beer now a dimmed buzz, I felt stupid content. Like my life was one long smooth road. No bumps, no curves, not even a stop light.

4 The Phone Call

It was a couple weeks after Christmas break. I’d just come home from school and was in the kitchen grabbing a snack — two frozen mini-pizzas, a half-dozen cookies, a pound of milk. Mom was at the table examining some fabric she’d just dyed part “lantern orange” and part “tobacco gold.”

Maggie came into the kitchen limping.

“Hi, sweetheart,” said Mom. “How was your day?”

“What’s wrong with you?” I snorted.

“My leg’s really sore, okay?” she snapped.

“Wimp,” I added, and she slugged me.

“Ow.” She was surprisingly strong for a wimp.

“What did you do in gym today?” asked Mom, putting down her fabric.

I put the pizzas in the microwave to nuke for three minutes.

“We don’t have gym on Tuesdays,” said Maggie. She climbed onto a stool with a groan.

“Maybe it’s from skiing?” I said.

Over break our family had gone skiing for the first time ever, meaning snowboarding. I got the knack right away. Being a throbhead with no natural rhythm, Maggie couldn’t snowboard to save her life. She’d taken some pretty bad falls but never complained. Just got out there and beat herself up the next day, too. I’m not sure her brain knew she had a body.

“That was weeks ago,” she said.

“Maybe it’s taken this long for the pain to register.”

Maggie lifted her foot onto the other stool and examined her calf.

“I don’t see a bruise,” she said to Mom, “but there’s a bump. Here, feel.”

“We should go skiing over March break.” I’d found out that Nat was going up with Erin’s family.

Mom felt Maggie’s leg. “A ganglian cyst, most likely, Magpie. They’re harmless.”

Poster Boy

Poster Boy